Wakandan Urban Planning

Black Panther’s production design imagines how spiritual tradition can inform community focused & environmentally conscious urban planning

Hello! This is part of my zine collection BLOCKS where I explore neighborhoods, urban planning, and community centered design.

Superheros of the Marvel cinematic universe might be the unintended result of science (Hulk), use incredible technology (Iron Man), or call on esoteric spiritual magic (Doctor Strange) to fuel their strength—some are themselves gods (Thor). Black Panther’s strength comes from two sources: incredible technology and traditional spiritual knowledge. Mirroring the superhero himself, Wakanda is a super-place—further advanced than other civilizations, but without social inequality.

How did Wakanda become so sophisticated yet retain community? Wakanda draws its strength from the same power Black Panther does, melding futuristic technology to be in-tune with the natural, spiritual world. The production design visualizes Wakanda’s ecological responsibility and community focused culture through the socially integrated technology, public transit system, and lighting. These qualities stand in stark contrast to other settings in the film. Traditional indigenous knowledge might be looked to for land management, but never for urban planning; Wakanda’s design envisions what that might look like. An alternate to abandoning spiritualism for technology, Wakanda leverages traditional culture to inform a positive vision of the future.

Technological Equity

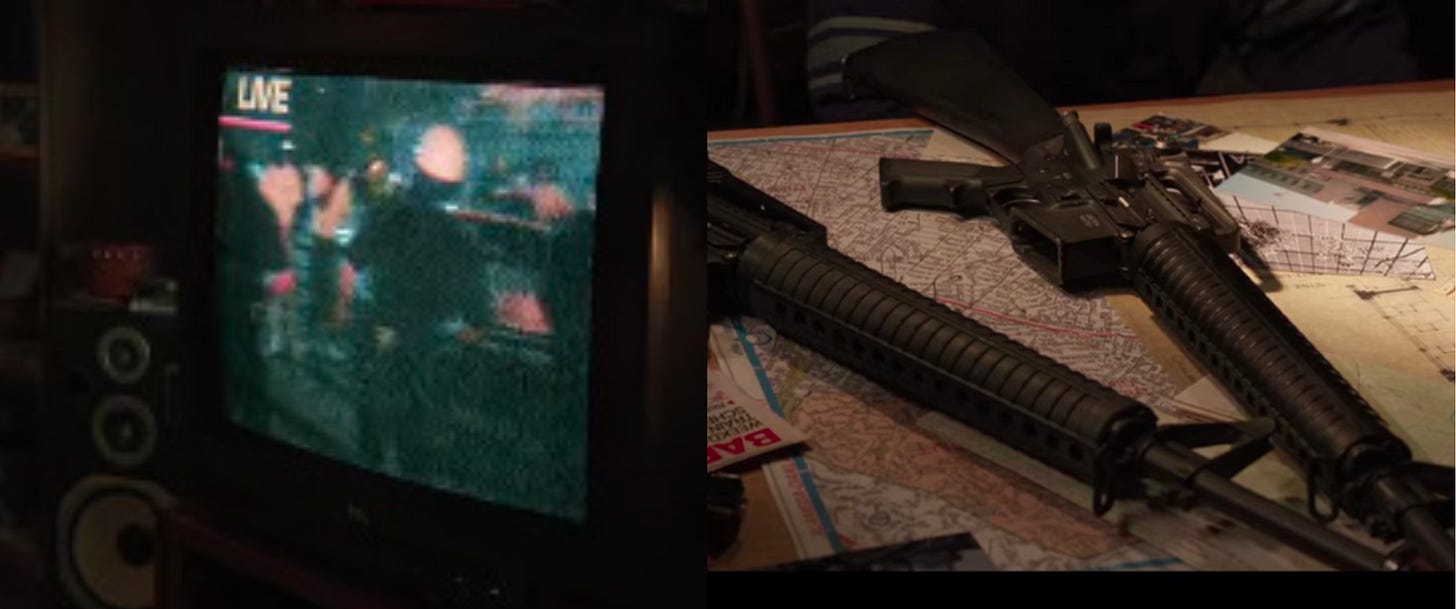

Marvel-America has a large tech-gap. Iron Man gets to play superhero because he is super-rich and can afford a weaponized suit, while the children of Oakland play with a broken basketball hoop. If Iron Man represents the glory mass wealth can produce, Oakland is the flip side of inequality. Entering the Oakland apartment in Black Panther, the first technology we see is an antiquated television showing staticky film of rioting. The next shot focuses on machine guns laid across the table. These two pieces of tech illustrate that this society is not a peaceful one—citizens live in a warzone.

In her interview Building Wakanda, Black Panther production designer Hannah Beachler makes it very clear she designed Wakanda’s to tell a different story: “..to be this super technologically-advanced you also have to have enlightenment in order for everybody to not kill each other, beyond greed, beyond Western ideologies, capitalism… connected as a society… we take care of each other.” Wakanda’s tech tells a very different story than Oakland’s. Citizens are casually seen using the same Kimoyo beads the king and his guard wear. The technology appears to be enabling human interaction rather than creating the distance it does in our world. Friends walk together discussing a sports projection, and a woman smiles as she snaps a photo of a friend.

Community Through Transportation

When we compare a place’s use of cars to public transportation, we start to see the culture’s prioritization of individualism versus community good. Access to affordable, reliable transportation is a key factor in uplifting people from poverty and public transit is more ecologically sustainable than cars.

It is no accident that special attention was paid to transportation in the production design of Wakanda. Wakandan transit respects land stewardship while also bolstering the community. Though never the focus of the composition, every urban scene shows multiple forms of transport servicing the city. Our first view of Wakanda reveals boats, trains, and the flying vehicle the characters ride. The market scene shows details of the street itself. Immediately, a high speed maglev enters from the right and a tram car enters from the left. Grass runs alongside the track where pedestrians interact as they walk to their destination. The maglev returns later as the setting for the climax of the film. Wakanda has boats, trains, and trams. Conspicuously absent?—Cars! Cars disassociate us by separating us into private spaces. Public transit not only supports wealth equity, it enables socialization by bringing us together. Pedestrians and tram riders in Wakanda are seen happily chatting.

Oakland’s transportation sets a strong contrast. Kids play on an asphalt parking lot which sits next to a large affordable housing complex. There is plenty of room for basketball because there are not nearly enough cars to fill the lot. The building clearly houses many more families than there are cars, signaling that most residents can’t afford to own. Cars zoom by but none stop—if you can afford a car you don’t live in this neighborhood. A bus drops off residents revealing the main method of transport, inner-city buses, perceived as unreliable and unsafe. Generally, Americans avoid buses if they can afford to. Buses are a stop-gap in a nation dominated by cars. Cities that prioritize reliable mass transit and unpolluted air have trains. This second-class access to transportation highlights cultural differences between Oakland and Wakanda and its impact on urban planning—America prioritizes the individual not the community. Public transit, especially for the poor, is an afterthought.

Busan’s transport also contrasts Wakanda’s. Compared to America, Korea boasts an advanced public transportation system, featuring high-speed trains and extensive metro. That however, is not shown in Black Panther which presents Busan as a city of cars. The first street scene centers a car in the composition, and later the fight scene focuses on an extended car chase. Wakanda could never host a car chase since it has rejected cars

.

Lighting the Path to a Sustainable Future

Alexandria township was the only neighborhood in apartheid South Africa where indigenous people owned property. The Johansburg government ignored its infrastructure, and it was without electricity until the early 2000’s. Once known as Dark City, Alexandria is now known as Maboneng: a place of lights. (Maboneng Township Arts Experience) This joyful renaming highlights that, around the world, electric light glowing in the night is associated with advancement. It is quite interesting that the futuristic city of Wakanda is never shown at night.

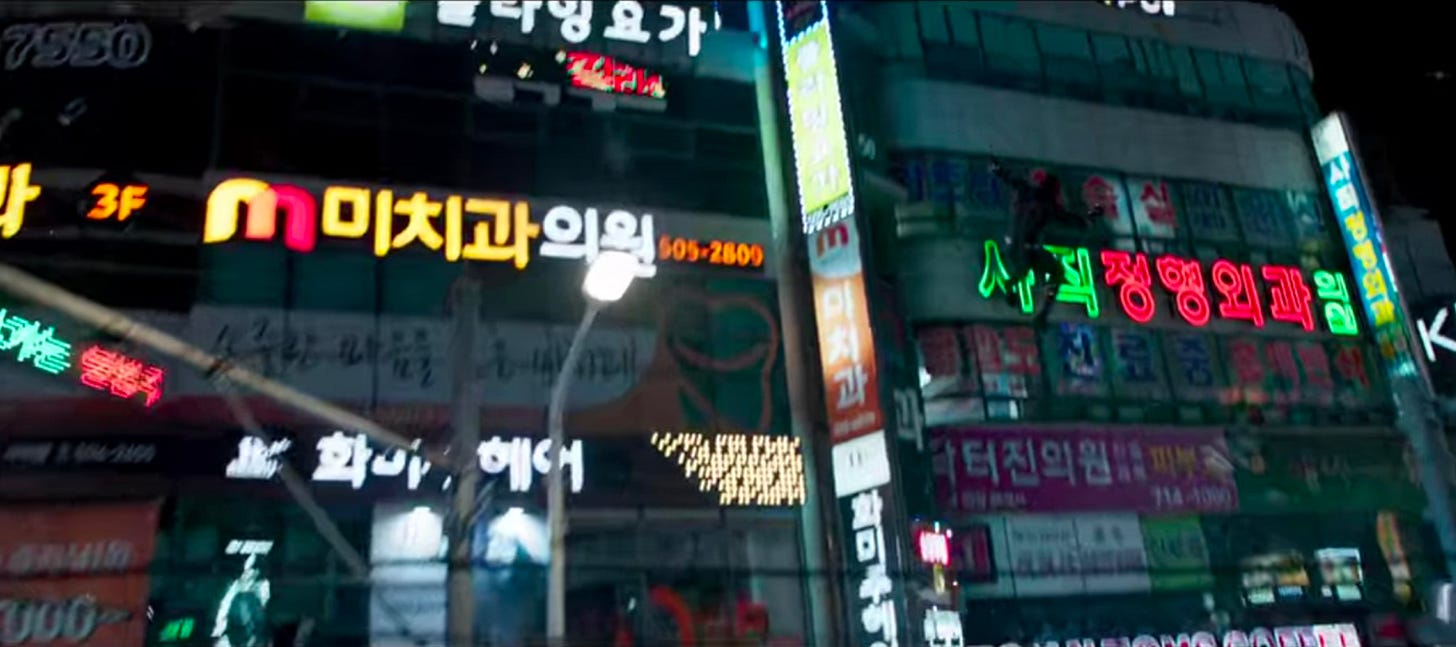

It is night time in Busan. Like Wakanda, we see a city on the water. The camera perches at the top of an architectural skyscraper boasting hundreds of lit windows, then dives into the city below. We expect advanced cities to be covered with colorful, glowing advertisements, like Times Square or Tokyo. Busan does not disappoint; colorful, bright billboards act as light sources. This lighting creates the immediate impression that Busan is an incredibly modern city.

The Wakanda skyline is only shown lit with daylight. I speculate that by our sensibilities it wouldn’t appear ‘modern’ in the dark. Wakanda lacks eye-catching, colorfully lit advertising since there predatory capitalism does not exist. Ecological sustainability might also account for a dark cityscape. We can understand this through example: Panama City has many beautiful skyscrapers, but something more than interesting architecture makes the skyline unique. Walk through the city before the sun rises; you will see… nothing. The skyline is barely legible, slightly darker shapes against a dark sky. By necessity, a city designed to have low environmental impact is dark at night. Light pollution is an environmental issue that goes beyond emissions and energy use, it confuses migratory patterns and harms wildlife. We associate darkness with rural areas—stars are only visible far from civilization.

I bet you can see the stars from Wakanda; a sign of their advancement and environmentalism, not lack of infrastructure.